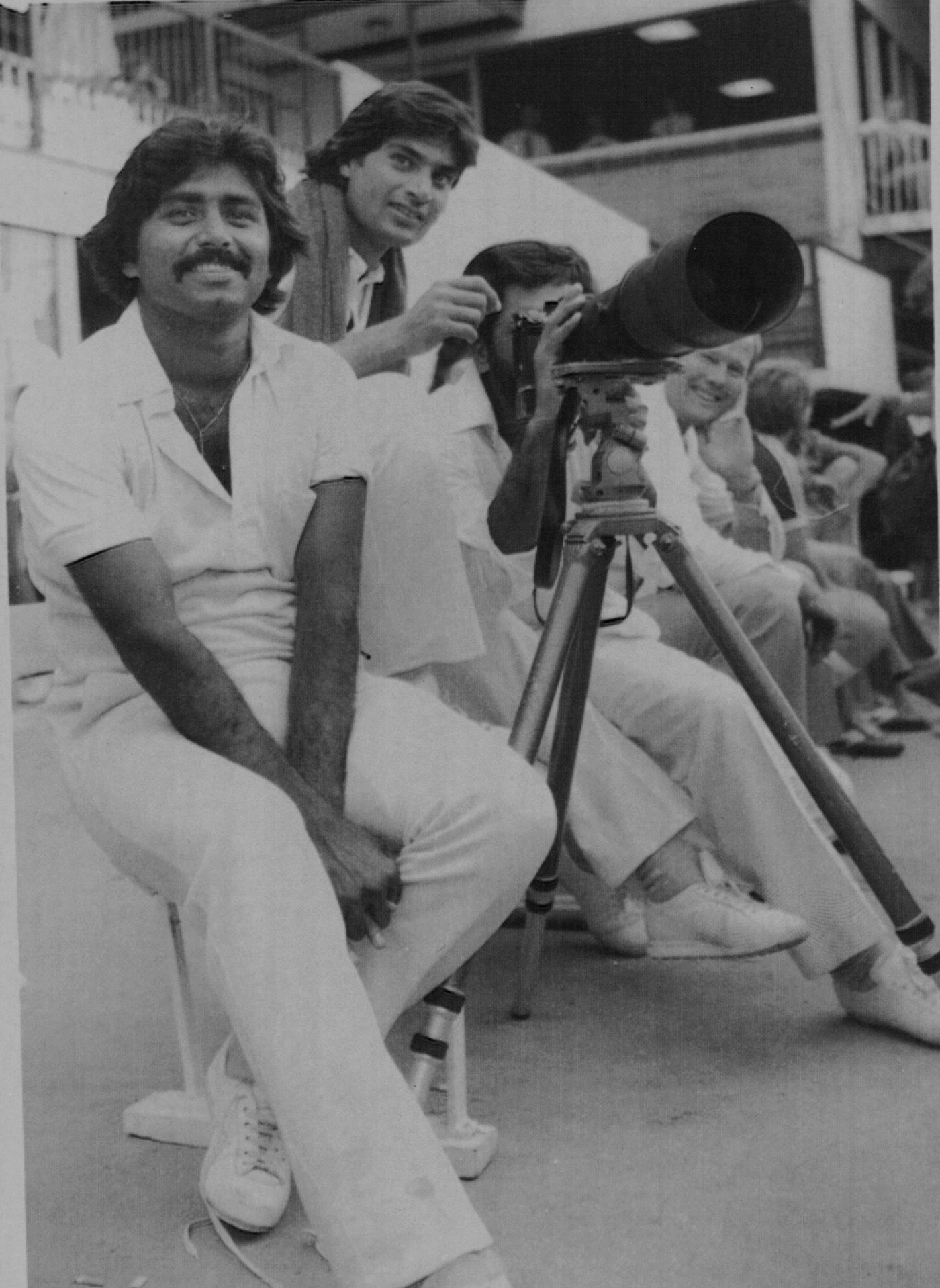

Javed Miandad’s last-ball six during a prior competition made history in the world of cricket. I well remember running into Sunil Gavaskar and Javed Miandad in the Sharjah Intercontinental elevator. They were both present for that historic final. Legendary cricket players from two countries that love the game gathered there.

Sunil Gavaskar, who never misses an opportunity for fun, couldn’t help but take a lighthearted jab. He questioned Miandad, “So, how many millions have you already made on that six?” with a glint in his eye. It wasn’t hyperbole to say that Miandad’s historic shot had sparked a torrent of presents, tokens, and awards. It is reasonable to say that it is the post-WG Grace period of cricket’s most lucrative strike.

Even while it may be difficult to put a precise dollar amount on Miandad’s windfall, its effects were felt emotionally in both Pakistan and India. India, the current World Cup champions, struggled, only winning 19 of their subsequent 62 One-Day Internationals (ODIs) against Pakistan. It took them another ten years before they were able to beat their rivals twice in a row. On the other hand, Pakistan’s cricketing fortunes improved dramatically, reaching a zenith with their World Cup victory in 1992. Up until 1993, they only lost one Test series, and from then until April 1999, they won 20 of the 36 bilateral ODI series.

Cricket has never been a sport where the impact of a single six was more obvious, be it psychologically, emotionally, or financially. Osman Samiuddin skillfully wove together threads of Pakistan’s evolution over the past 15 years to depict the impact of that one shot in his exhaustive history of Pakistan cricket. It contained the birth of celebrity players, the growth of player influence, the popularity of the game, forward-thinking administrators like Abdul Hafeez Kardar and Nur Khan, the introduction of departmental cricket, the development of television, and the entry of additional funds. A golden age for Pakistan, the most glorious age they had ever known, emerged on the other side.

As is frequently the case, fans came up with their own explanations for such outcomes, ones that went beyond individual genius or team dominance. There is a widespread notion in India that “Pakistan cannot be defeated on a Friday.”

Even though it may seem unjust to reduce a 22-person cricket match to a single ball and a single stroke, the game had been mainly one-sided up until that crucial point.

Kapil Dev, the captain of India during that crucial game, reflected on the incident in a later televised interview with Wasim Akram. “Even when we remember that today, we can’t sleep,” he said. The confidence of the entire team was destroyed by that loss for the following four years. Beyond the players, the effect reached the cricket writers themselves. My supervisor claimed that Chetan Sharma, who bowled the final over, should have sent a ball near Miandad’s foot so that it would roll in his direction (underarm bowling was already prohibited at that point). Miandad might have found a way to score off that as well, given his performance that day. By the final ball, Pakistan needed to score four runs.

That final over perfectly captured the essence of cricket: runs, wickets, dismissals, close calls, and finally the iconic match-winning hit. It’s important to remember, though, that the game itself wasn’t always exciting. India dominated right away and maintained its advantage for 99 of the 100 overs. Before that spectacular last over reversed the tide, the outcome seemed certain.

Ramiz Raja, a participant in that titanic battle, simply summed up the match’s course in a televised interview: “I believe the game started about 9 am. India led from five minutes past nine until the last five seconds. Then it made a turn.

Pakistan had 235 for 7 going into the final over and needed 11 runs to win. Miandad was destined to favor a leg-side heave because to his open posture and bottom-hand grip. His first attempt went long-on, where Kapil fielded and threw, causing Akram, who was trying a second run, to be run out. Long-on boundary was reached by the second ball. At short fine leg, Roger Binny made a fantastic stop of the third ball, only allowing one to be conceded. The following ball was bowled out to wicketkeeper Zulqarnain. Tauseef Ahmed ran for a single on the sixth ball and had a chance to be run-out, but India’s greatest fielder, Mohammad Azharuddin, missed the opportunity. Then it made a turn.

Pakistan needed 18 runs from two overs and then 31 runs from three overs. In the 1980s, the odds were in favor of the fielding side anytime the needed run rate was greater than six runs per over. The best bowler would normally bowl the final over 37 years ago. Captain Kapil, who could have bowled it himself, reasoned that the goal in the 50th over would be too high if they kept the 49th over tight. It wasn’t a crazy plan, because even today’s captains use a similar tactic.

Chetan Sharma, a 20-year-old who had previously claimed three wickets, received the ball as a result. The only bowler with a remaining over was Ravi Shastri. “I was the junior-most player and didn’t expect Kapil Dev to call me to bowl,” Chetan subsequently admitted. I thought I would bowl a short-pitched delivery as I started my run-up. I came to a stop and turned around. I was going to bowl a yorker, but I changed my mind as I got closer.

The outcomes of mid-flight changes of heart might be unexpected, as seen by several fantastic cricketing tales. They might, however, also cause problems. That yorker never touched down because Miandad anticipated it and positioned himself just in front of the crease. The match ball was carried past the deep midwicket boundary by the leg-side heave of the full toss, which came in easily at thigh height.

The fans frequently target a certain player when India loses to Pakistan. Goalkeeper Mir Ranjan Negi was held responsible for India’s hockey team’s 1-7 loss to Pakistan in the Asian Games championship four years previously. He described experiencing tremendous public abuse, and the strain that followed even made him think of committing suicide. In his own words, Chetan Sharma went through “one of the worst times a cricketer can go through.”

But a few months later, when India won the 2-0 Test series in England, he made up for it by taking 16 wickets at an average of 18.75, making him the most productive bowler on either side despite missing the second Test due to injury. He took ten wickets in the third Test, which resulted in a draw. He scored the first hat-trick in a World Cup a year later. He presided over the national selection committee in more recent times. However, as is sometimes the case in sports, the names of both the winner and the defeated from that particular encounter remained inextricably connected.

The competition had been so one-sided up until that moment that the final over carried the promise of being an entertaining battle, even though it may seem unfair to reduce a match comprising 22 players to a single ball and a single stroke. The opening pair for India, Sunil Gavaskar (92 off 134 balls) and Kris Srikkanth (75 off 80), put together an impressive 117-run partnership. Gavaskar and Dilip Vengsarkar then contributed an additional 99 runs. Together, Imran Khan and Wasim Akram took five wickets.

Mohsin Khan’s 36 was the second-highest score in Pakistan’s response. Before the dramatic final over, Miandad, who is famed for his ability to score runs with singles and doubles, was calmly and effectively extending his innings.

For years to come, Miandad’s historic 116 off 114 balls, which included three fours and three sixes, transformed the nature of the India-Pakistan cricket match. He remained a reliable batsman, scoring hundreds in Test matches against the West Indies, England, Australia, and New Zealand, including a double hundred at The Oval. He was essential to Pakistan’s World Cup success in 1992.

At the age of 39, Miandad was a shell of the player he had been for the previous 20 years when he arrived in Bangalore for his sixth World Cup. Miandad was battling to play directly to the fielders, a far cry from his best, according to the commentators. Having proclaimed his retirement in 1994, Miandad had not played for two years, as noted by Gavaskar. Gavaskar and the rest of India were aware of Miandad’s abilities.

India did not collectively exhale with relief until Miandad was bowled out for 38 after requiring 64 balls, ending their quarterfinal match. I did something in the press box that I had never done before. One of the greatest batsmen of all time was cheered into the pavilion as I got to my feet.